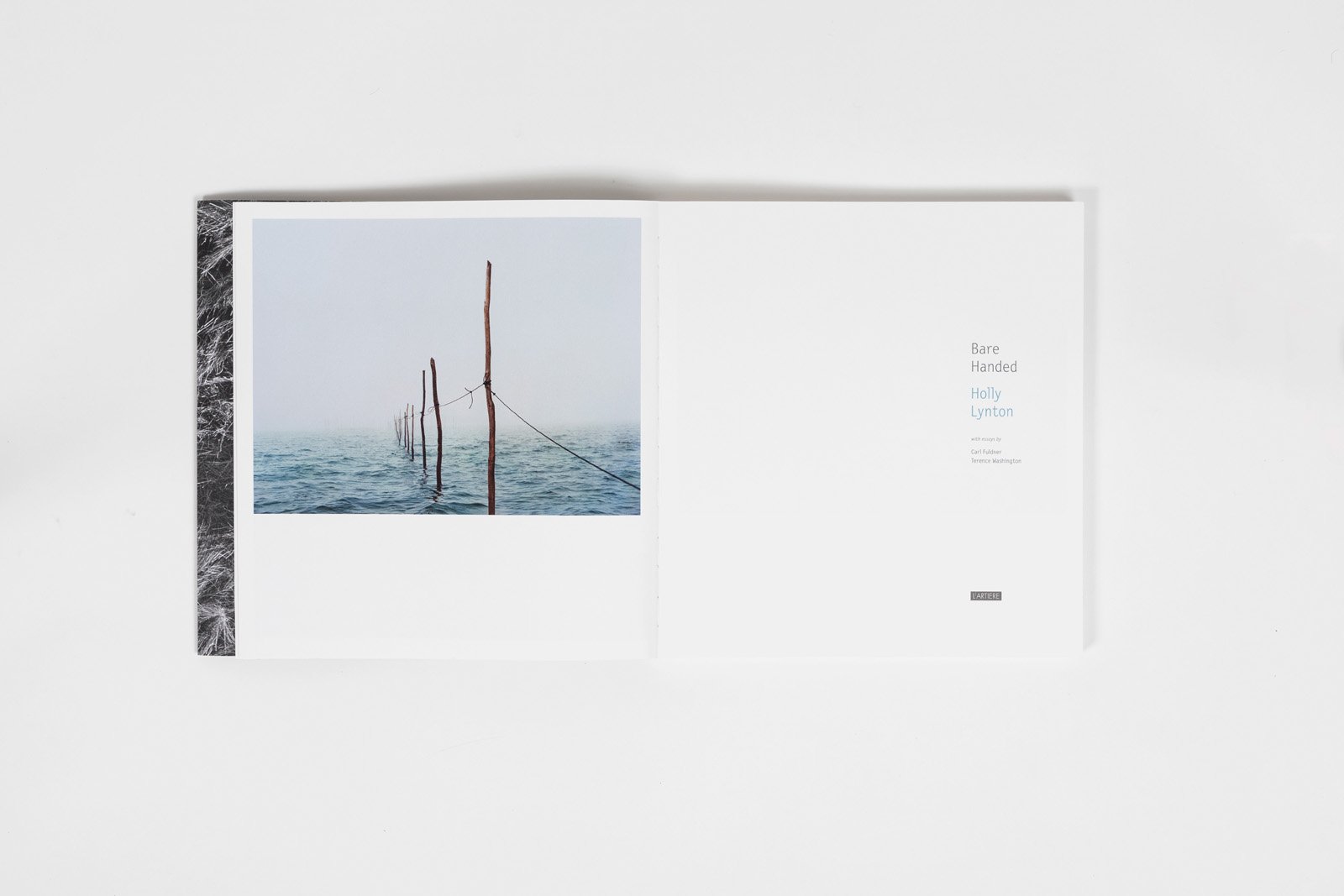

Bare Handed

Photographs by Holly Lynton.

Published by L’Artiere Edizioni, Bologna, Italy.

Designed by Margaret Bauer.

Essay contributions by Terence Washington & Carl Fuldner.

10.5 x 11.6 inches, 136 pages, 78 images.

Softcover with hardcover slipcase available at Mass MoCA.

Special edition of 25 + 8 x 10 c-print (available).

Library Collections

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Thomas J Watson Library (Metropolitan Museum of Art), Boston Athenaeum, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Hirsch Library (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Tate Library (Tate Museum), Frost Library (Amherst College), CWMARS (Worcester), Morton R. Godine Library (Massachusetts College of Art and Design), Fine Arts Library (Harvard University), Columbia University Libraries, Firestone Library (Princeton University), Myrin Library (Ursinus College), Wallace Library (RIT), Margaret R. and Robert M. Freeman Library (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts), National Gallery of Art Library, Ingalls Library (Cleveland Museum of Art), Perkins Library (Duke University), Michigan State University Library, Ryerson & Burnham Libraries (Art Institute of Chicago), Columbia College Chicago, Washington University in St. Louis, Bethel University Library, New York Public Library

Reviews

-

“Alligator, shrimp and beaverslides … Holly Lynton’s beautiful photographs reveal the spiritual state of being that emerges from nature and tradition. Returning to specific communities year after year, Lynton moves beyond mythology to reveal a complex social landscape suffused with tradition but unburdened by nostalgia. She says: “Being on the shrimp boat, it wasn’t just the work of shrimping, it was the sea, the weight of the humidity in the air, and the dolphins and birds following us.”

-

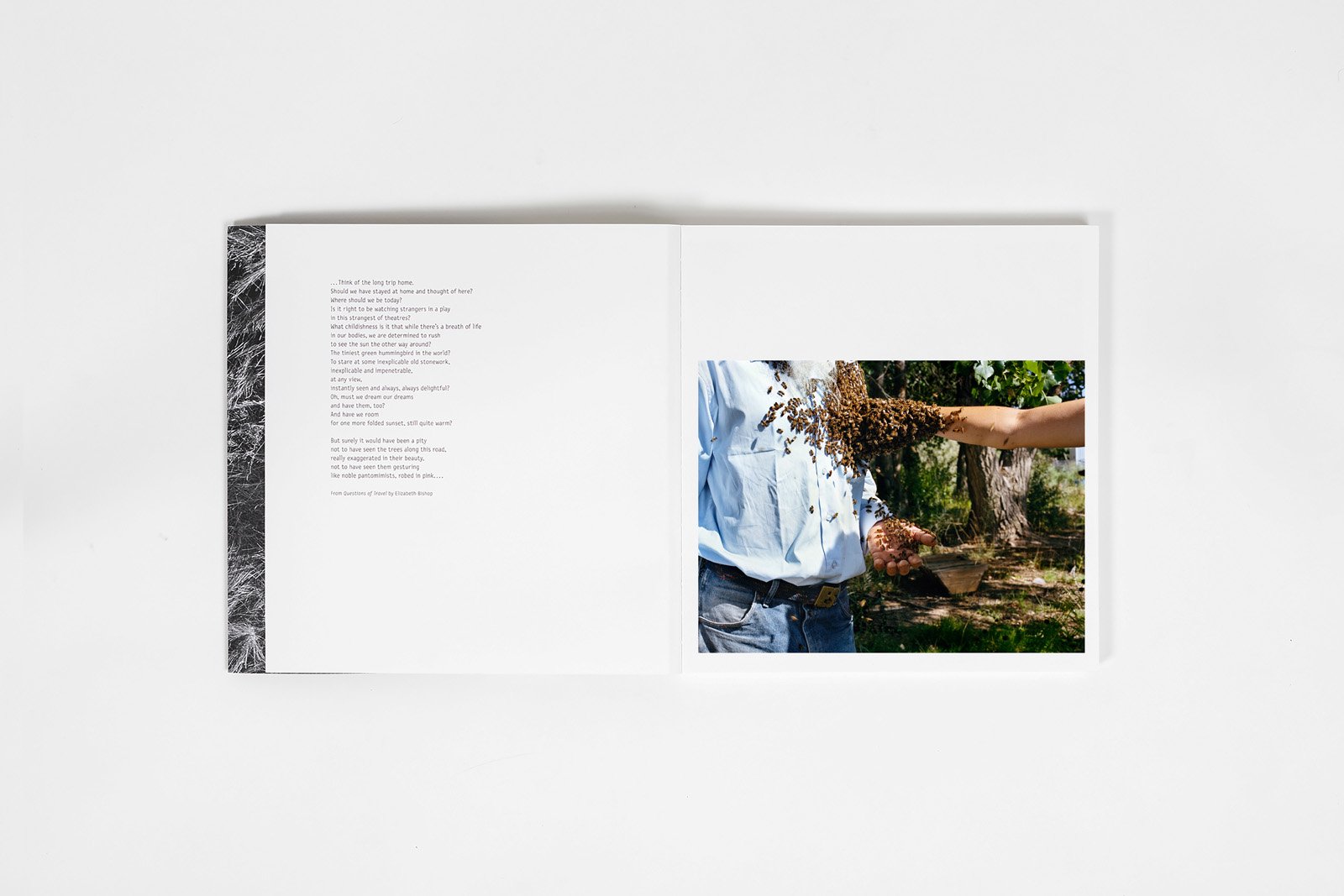

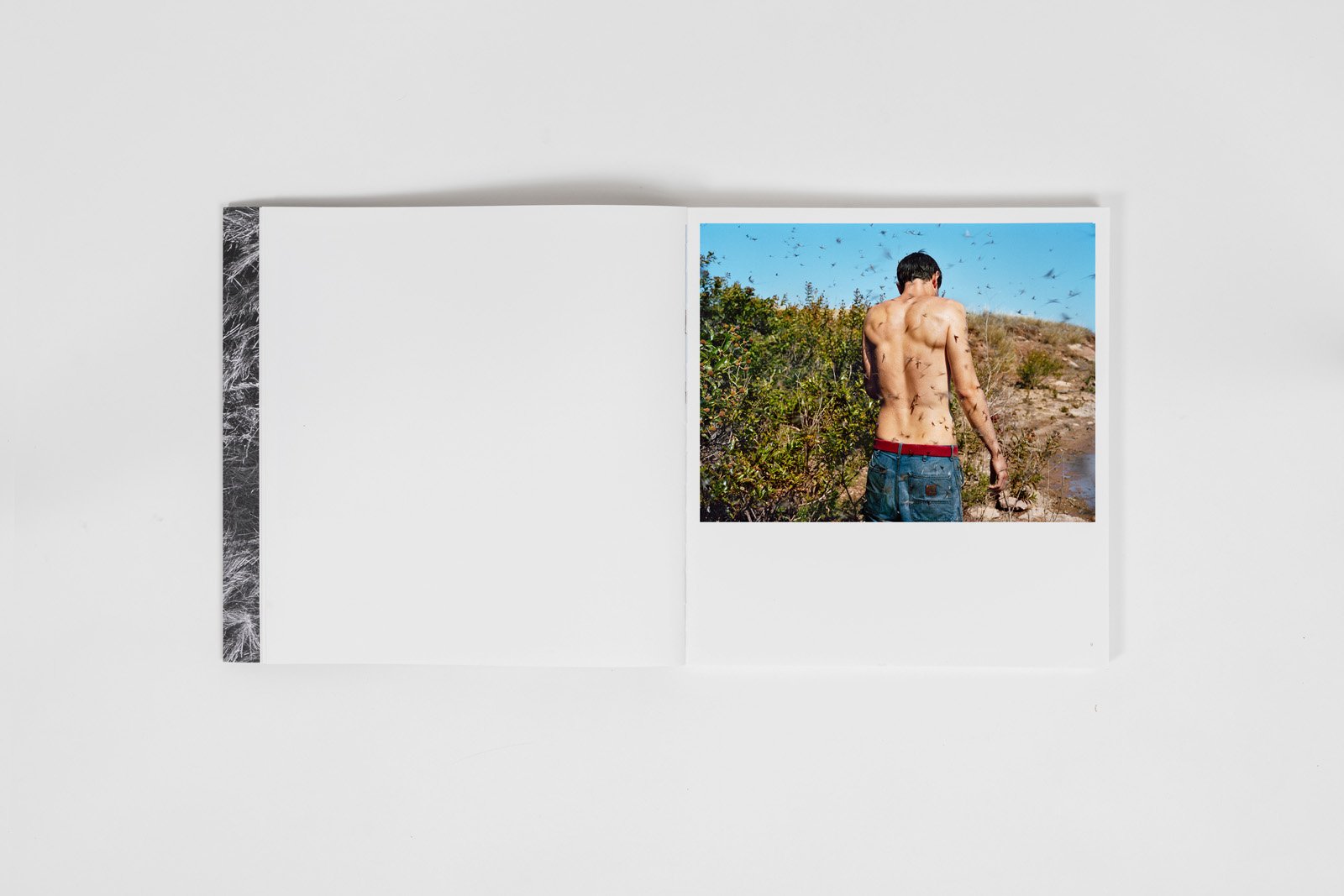

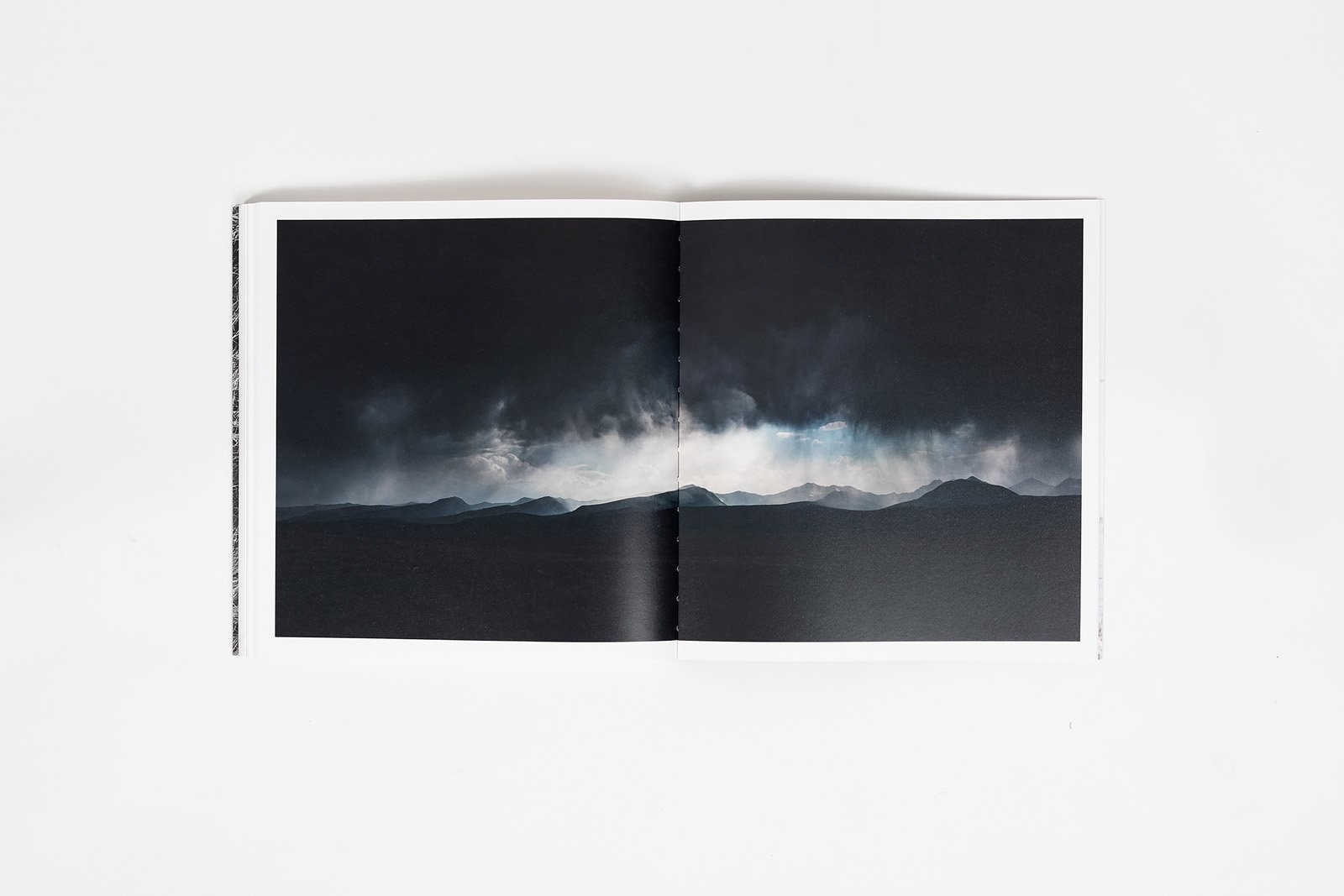

“The photobook immediately stands out as a thoughtfully crafted object. Bare Handed is a softcover book, hosted inside a slipcase with a photograph of a silo covered in leafy green vines, immediately putting nature forward; the title and the artist’s name are placed on the book spine. As we get the book out of the slipcase, its front cover shows the shirtless back of a young man walking in the wild, his skin covered with drops of sweat and a cloud of mayflies flying around him and landing on his body. The cover of the book then unfolds to reveal a pair of weathered, working hands (with soiled and cracked skin) placed on top of freshly picked spring onions, providing an echo of the book’s title and a tangible example of healthy work. Inside, the photographs vary in their size and placement on the pages, creating a dynamic and unexpected visual narrative, and the captions are placed at the very end of the book, in a simple list.”

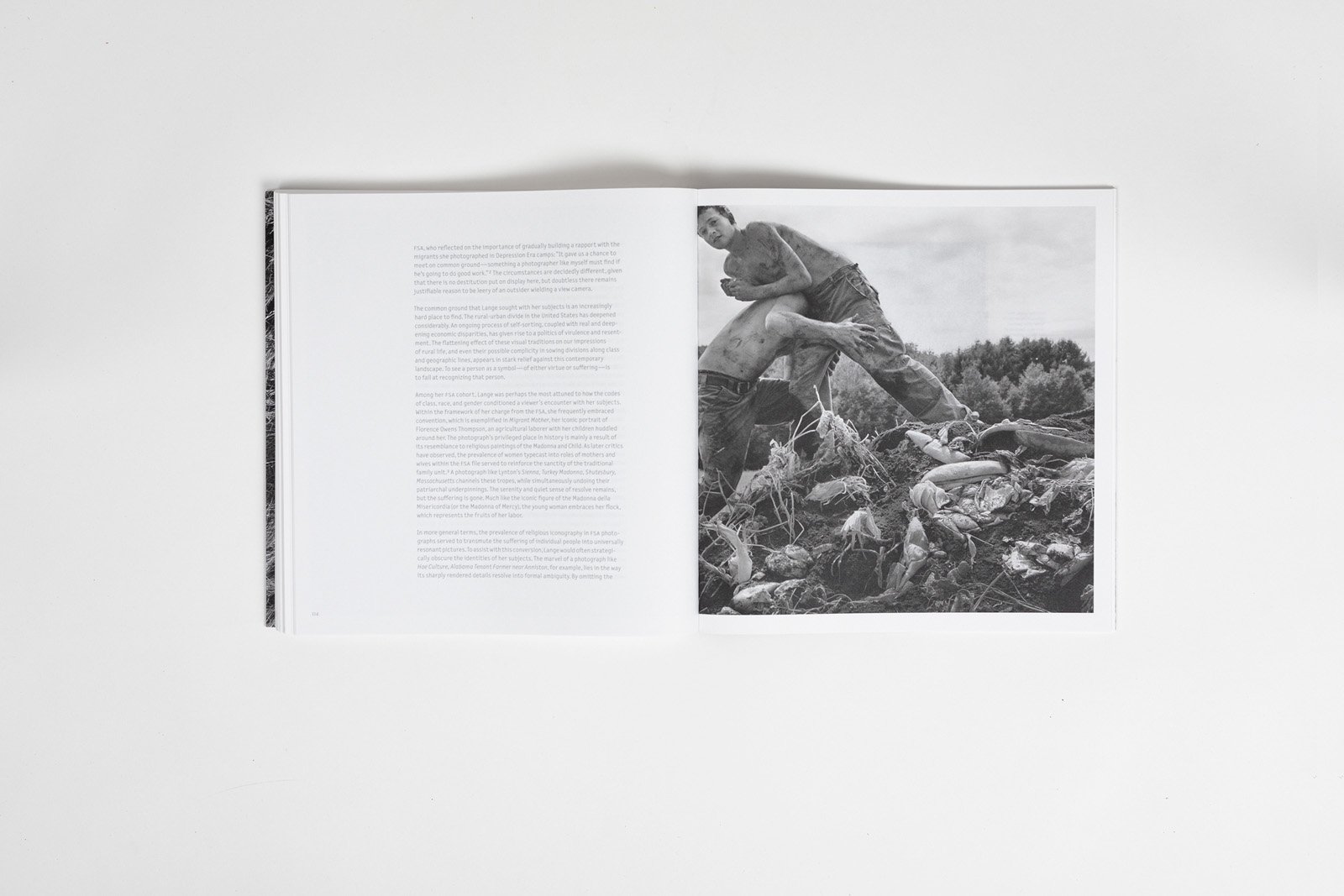

Gestures and movements are important to Lynton, connecting her to her childhood experience as a ballet dancer. A picture of two shirtless young men caught in either a playful tussle or helping support on top of a compost pile is paired with a more serene shot of a young woman relaxing on a tree branch by the water, while a young man sits underneath her on a rock; the gentle dappled sunlight makes the scene even more idyllic. And Lynton’s image “Skipper, Christian, Catfish, Temple, Oklahoma” captures another tender moment when a father is pulling a hefty catfish out of the lake with his hands, while his son is right beside him in the water. Many of Lynton’s photographs capture a kind of subtle mysticism present in everyday life, and in his essay, Terence Washington notes that “by incorporating recognisable symbols, Lynton invokes cultural memories, the touchstones that form us as individuals and unite us through shared experience.”

In this way, Lynton’s photographs celebrate her subjects and their spiritual convictions. Her series stands in contrast to the 1930s surveys of rural life performed by ten photographers commissioned by the Farm Security Administration. They documented the struggle of rural America, its poverty and its despair, and a number of their images, like “Migrant Mother” by Dorothea Lange, have become emblematic. Lynton’s pictures search for different mood, where people and nature are in better equilibrium.

Over the years, Lynton has built lasting relationships with the people in her pictures, and her photographs pay respect to their courage, dedication, and passion. Her visual narrative, with its distinct aesthetic and quietly optimistic sensibility, portrays an impalpable set of connections that weave the land back into our lives. Each photograph brings in a genuine personal story, and linked together, they remind us of the complexities and nuances that fill life in that rural America. That engaged and positive message helps to make Bare Handed a solidly good and exciting photobook.”

-

“La beauté et la simplicité des images d’Holly Lynton, la délicatesse de ses lumières et de ses couleurs construisent, page après page, un portrait nuancé de la vie rurale dans l’Amérique de xxie siècle. L’autrice nous révèle ici un paysage social complexe, imprégné de tradition, mais sans aucune nostalgie. Un travail réalisé dont une décennie pour que se tissent, au fil du temps, les liens organique reliant les hommes, les animaux et les paysages.”

-

“Flannery O’Connor, titan that she was of the Southern Gothic genre, once wrote, ‘The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.’

This seems to be the guiding principle of Holly Lynton’s most recent book, Bare Handed. The 78 photographs within this volume take us throughout areas of the United States, each marked by agrarian and piscary labor. By contrast, Lynton’s photographs have an ease about them, despite their meticulous formal composition. Each image presents, as Terence Washington writes, the “moments between moments,” as though captured by an unseen presence there with the subjects.

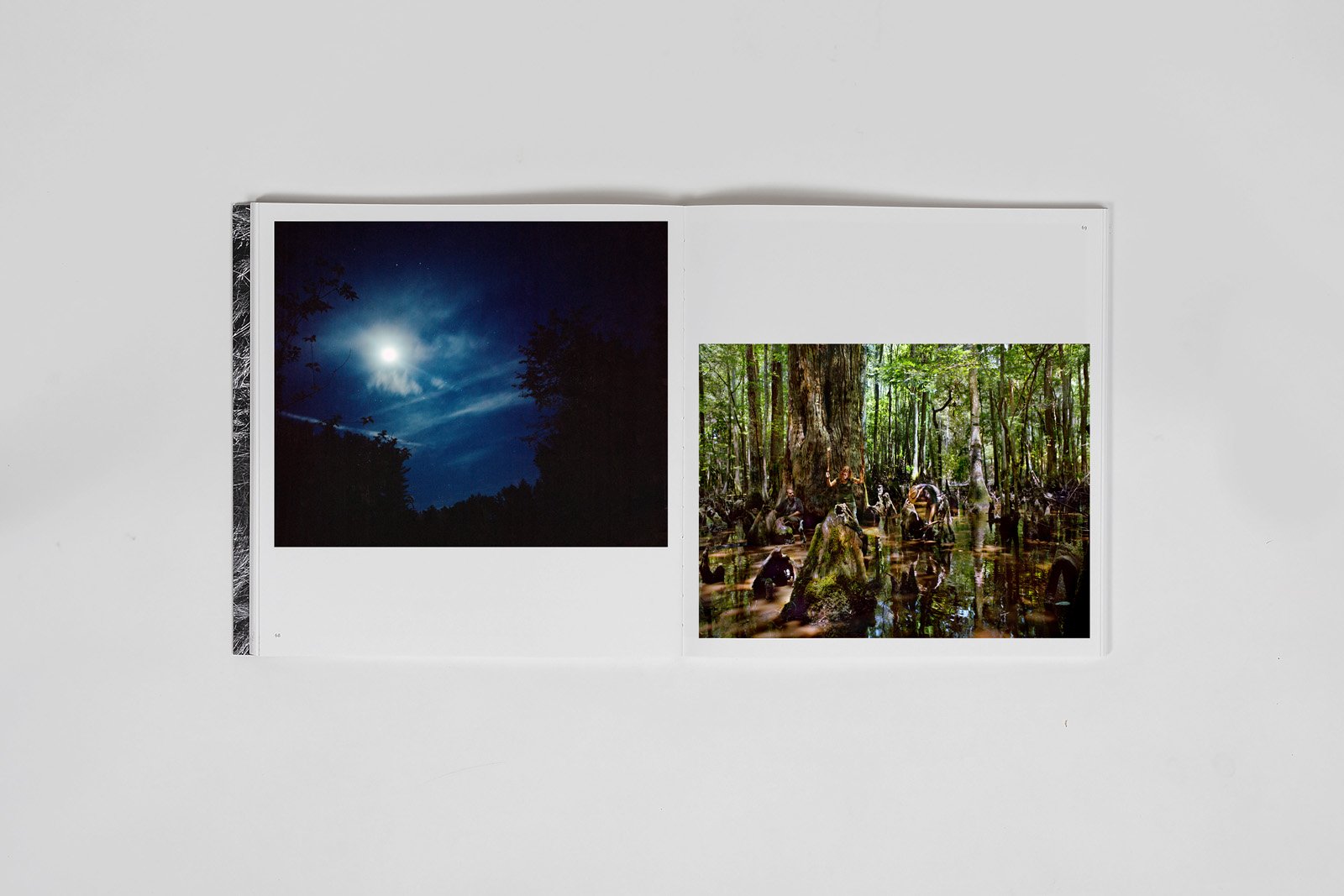

The presence of biblical imagery is unmistakable in Lynton’s photographs. Entire stories and verses are contained in a single image, bolstered by the presence of others. A shepherd lays amongst her flock, her hair covered with a kerchief and her hand on a wooden crook, the long light of the day turning wool and skin alike a rosy gold; the smoke from a burning branch turns sunlight into blue crepuscular rays; a man and woman bask in the shade of a tree overhanging the Bronx river, apples and their cores strewn about the muddy banks.

Through these photographs, a kind of creation myth is set forth, and Lynton expertly plays with this romanticized, pastoral vision of American Life. Using these utopian, idealized images of the agrarian experience, she creates a dissonant conversation with images that contain a great deal of violence. Swarming insects alight on the bare skin of a man’s back, his head bowed against the beating sun; monstrous, mottled catfish are dragged from a river; opposite the Edenic couple, on the facing page, two young men fight atop a compost pile…

Lynton works within a visual history not only of religious artwork, but also one set forth by her photographic forebears, the photographers employed by the Farm Security Administration. There are echoes of Lange, Evans, Rothstein in these images, of the hardships of the Dust Bowl. There are moments of pure transcendence in the photographs, alongside the deep scars of racism and its legacy that remain etched on the terrain called the United States. Bare Handed traverses the moments that fall between the brutality and the divinity of the everyday, ruminating on a painful past and the possibility of the future.”